PNW Tree ID Sign Project

The PNW Tree ID Sign Project builds off the interpretive-sign tradition of identifying trees in situ as an educational program for trail users. This project specifically focuses on tree species found in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The project’s tree selection covers a vast spectrum of species curated from Oregon’s high desert pine country to the coastal sitka ghost forests of Washington. The series includes iconic species, such as giant sequoia, as well as lesser known diminutive species such as the mountain hemlock. The graphic design of the mixed-media signs (recycled wood, paint, and lasers) is intended to tell botanical tales that are simultaneously ancient, unfolding, and complex in their relationships to Homo sapiens. Each sign identifies the species through the tree’s cone to communicate a cultural narrative as a means of making the arboreal information both accessible and memorable. The sturdy wood signs are built for easy installation and offer land stewards a tactical programming opportunity for an offbeat temporary interpretive trail. The signs are light enough to carry into remote locations with relative ease, yet durable enough to weather the climatic conditions of the Cascadian forest ecosystem.

The PNW Tree ID Sign project was documented with a humble DIY publication known as the Unfinished Book Bureau. The intention behind this publication was twofold; to showcase the dozen PNW Tree ID Signs, as well as provide insight into the project’s creative development, from initial design-narrative concept and pointed use of graphic tropes to fabrication method and output, to the final installation in the field. The interdisciplinary collaborators hope the work inspires others to create similar site-based landscape appreciation projects.

To date, the signs have been exhibited at the Trustman Art Gallery at Simmons University, the University of Oregon’s College of Art and Design, the Center for Art Research, Oregon State University’s College of Forestry, and guerilla installations throughout the University of Oregon campus and Hendricks Hill Park in Eugene, Oregon.

Collaborators: Vinnie Arnone, Rachel Benbrook, David Buckley Borden, Asa DeWitt, Ashley Ferguson, Evan Kwiecien, Isaac Martinotti, Madison Sanders, Blake Schouten, Nancy Silvers, Dr. Fred Swanson, and Ian Escher Vierck.

This project was funded by the Fuller Initiative for Productive Landscape at the University of Oregon, Oregon State University Foundation’s Andrews Fund, and the sale of artwork on this website.

PNW Tree ID Signs, Ghost Forests Exhibition, array of nine mixed-media signs, recycled oak flooring, India ink, acrylic paint, and lasers, dimensions vary, Trustman Gallery, Simmons University, Boston, Massachusetts, 2022.

Pseudotsuga menziesii, Douglas-fir, has a large range west of the Rocky Mountains, from the northern tip of Vancouver Island down to the coastal and mountain ranges of central California. It prefers elevations from sea level up to 5000 feet, sometimes more. Its needles are spirally arranged, with a slight twist at the base. Its mature cones are tan and have a unique 3-pointed bract that extends beyond the scales which evokes an abstract form that looks vaguely like the tail and hind feet of a frantically scrambling mouse attempting to hide just beneath the scales. Douglas-fir trees yield the most amount of timber in North America, making the Doug-fir one of the most economically important trees in the world. The tree is closely associated with the people and timber industry of the PNW, so it is no wonder that our friend Dougie is the state tree of Oregon, and is still the best-selling wood species at Jerry’s Hardware in Springfield, Oregon

Picea sitchensis, Sitka spruce, occurs within a thin strip on the Pacific Coast of Oregon into Alaska, often only reaching a few miles inland. It is a PNW costal icon, making its home along the shores and inlets of a moss covered, moist landscape. Its stiff and sharp needles are glaucus with two strips of stomata on the underside. The tan colored, medium-sized cones are soft, papery, and pale brown. When dry, these cones make the best, out of tune mini xylophones to run a finger across. The Sitka spruce was a central species of a nearly lost ecosystem, the tidal forest. Today, most of the tidal forests have been logged, diked, and converted to farmland and luxury seaside homes. What little remains of the Sitka spruce forests is a somber testament to Homo sapiens’ collective environmental values.

Other Oregon Coast ghost forests, such the Neskowin Ghost Forest were likely created when the Cascadia subduction earthquake in 1700 AD covered the tidal forest with debris from a massive tsunami.

Pinus sabiniana, gray foothills pine, is endemic to California and the Klamath Mountains eco-region of Oregon. The gray foothills pine can be easily identifiable by its tremendously large cones and long drooping needles. The infamously large cones of the gray foothills pine are specially adapted to the sloped and grassy environment it resides in.

After three to five years of staying on the tree branch, the foothill pine cone will detach and roll downhill (hikers beware). The falling cones are heavy enough to cause injury or death to Homo sapiens and have been nicknamed “widow maker cones” due to fatal tales of backcountry misfortune.

Pinus contorta, lodgepole pine, is a hard pine located from the shore of the Pacific Coast to the PNW sub-alpine mountains. The lodgepole pine can tolerate many harsh conditions, such as clay soils, freezing temperatures, and even the pumice ridden soils of central Oregon which can sometimes reach 140 degrees during the summer (Arno, 2020). Its egg-shaped cones are prickly and serotinous, needing fire to release its seeds. The cones’ size and mass make it a choice selection in the suburban sandlot game known as “pine cone war.” The fire-activated oblong cone is rumored to be the inspiration for the game of “Whack Bat” in the 2009 cult classic film Fantastic Mr. Fox. Due to the Andersonian association, the ‘Whack Bat’ pine strobili are coveted souvenir cones in Hollywood, California. The sign features a billow of smoke as a gentle warning to alert folks that they have entered the potentially dangerous Pinus contorta ‘Whack Bat’ zone. Trail users beware!

Pinus lambertiana, sugar pine, can be found throughout the mountains of Oregon and California in moist environments. Its needles are found in fascicles of 5. The overall form is recognizable for its large crown of majestic outreaching branches. Not only is the sugar pine the largest pine in the world, it also bears the largest cones of all pines, with the largest recorded specimen clocking in at an impressive 22 inches. No fooling! When green, the pendant cones can weigh two to four pounds, making them the weapon of choice for petty squirrels overhead.

There were several uses for the sugar pine. Native peoples ate and harvested the tasty seeds and used them in a variety of ways, including roasting, boiling, baking into cakes, or pulverizing into a nut butter spread. The sweet resin was chewed as gum sparingly due to its laxative qualities (Arno, 2020).

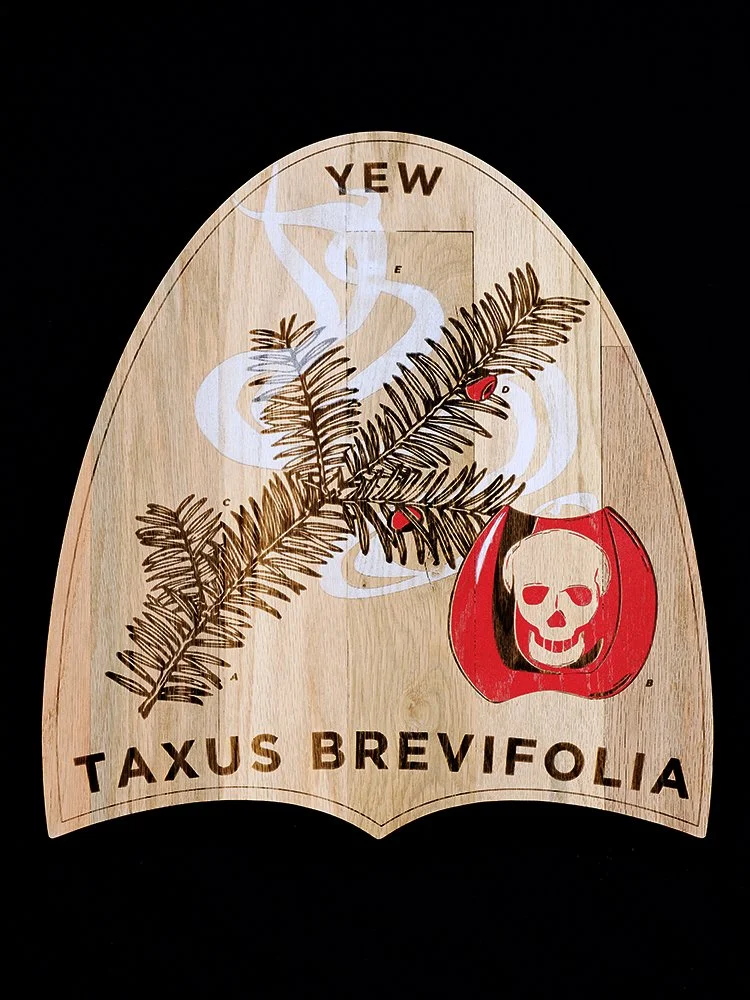

Taxus brevifolia, pacific yew or western yew, is a tree species in the yew family Taxaceae and is native to the Pacific Northwest. It is a small evergreen conifer, thriving in moisture dappled sun light, and tends to take the form of a shrub. With the passing of time, it will eventually take the form of an understory tree, hiding beneath the towering Douglas-firs and western hemlocks. It can be found sparsely in the southern Alaska Panhandle all the way down to the San Francisco Bay area, as well as extending east to the northern Rockies.

The pacific yew houses a legendary poison, which is toxic to humans, especially children. All parts of the tree are toxic, so kindergarteners beware on forest field trips! The yew is known for its small, violently red, berry-like cones also known as an aril. Only the female trees produce these pea-sized poison pills. Each aril contains one toxic seed surrounded by bead-shaped fleshy pulp. The needles are flat, double ranked, and deep green.

The whimsical-looking bark of the pacific yew appears to have leaped straight out of a fairy tale, as it is scaly gray on the outside and bright purple on the inside. During the 1990s the pacific yews’ bark was discovered to house the chemical known as Taxol (or Paclitaxel) that can inhibit ovarian and breast cancers. The chemical was extracted from trees in the Pacific Northwest for roughly ten years before pharmaceutical companies switched to agricultural plantations, later synthesizing the drug (Arno, 2020). This controversial harvest of a seemingly unforgivable poison allowed the shade loving pacific yew to come into the light of popular culture for a few years, helping cancer patients, before fading back into humble obscurity and avoiding prolonged exploitation.

Sources:

Arno, Stephen, and Ramona Hammerly. Northwest Trees. Mountaineer Books. 2020, pp. 30-35, 61-69, 83-91, 101-110, 117-122.

Jensen, Edward. Trees to Know in Oregon. Oregon State University. 2010, pp. 11-13, 20-21, 28-29, 36-37, 42-44, 107-108.

“Pinus strobus.” Edited by Christopher J. Earle, Pinus strobus (Eastern White Pine) description - The Gymnosperm Database, 6, Aug. 2023, Pinus strobus (eastern white pine) description (conifers.org)

“Pinus sabiniana.” Edited by Christopher J. Earle, Pinus sabiniana (Foothills Pine) description - The Gymnosperm Database, 26, Feb. 2023, Pinus sabiniana (gray pine) description - The Gymnosperm Database (conifers.org)